Beyond the Pioneer : Why Monitor’s next chapter on scale focuses on factors from outside of the social enterprise

I’m not an entrepreneur, not even close. But I’ve spent a lot of time with them. And believe me, they can be an introspective bunch. Even though they exude confidence and self-assurance, I’ve had enough conversations with social entrepreneurs to know that they toil daily with lonely questions such as: “Have I picked the right mission? Do I have the right management team in place? Are we presenting the best product at the best price?”

Innumerable academic business reports and case studies explore the interiors of businesses and plumb the depths of the questions above. But here’s one that looks at the outside factors that trip up even the most well-intentioned, and well-funded, entrepreneurs hoping to pay dividends in social and economic good.

Harvey Koh, director at Monitor Inclusive Markets, and I chatted back and fourth over email to dig a bit deeper into this study, Beyond the Pioneer: Getting Inclusive Industries to Scale, which he co-authored with Nidhi Hegde and Ashish Karamchandani. The report is the widely anticipated follow up to From Blueprint to Scale: The Case for Philanthropy in Impact Investing, created by Monitor and Acumen in 2012. The new report details the very real structural barriers that social entrepreneurs must overcome if they expect to go beyond their pioneering days and reach scale.

Scott Anderson: We’ve written quite a lot about From Blueprint to Scale on NextBillion. That report sought to expose the pioneer gap in early-stage support to firms developing new, inclusive business models. It called for greater enterprise philanthropy to help close that funding hole. Where does Beyond the Pioneer pick up from that report?

Harvey Koh: Beyond the Pioneer is really the next piece of the puzzle. Even as we were writing From Blueprint to Scale two years ago, with a strong focus on individual firms, we were aware that the firm represented only part of the picture, and that came from our programmatic work on the ground in India in trying to get specific market-based solutions to scale, in urban ownership housing, urban safe water access and rural sanitation. This part of our work is less well-known than our research output, but it has taught us so much about what it takes to actually implement these solutions. The overarching learning was that getting market-based solutions to real scale required us to look, think and act beyond the pioneer firm. When we shared this thinking with a number of partners similarly interested in scaling market-based solutions, it resonated strongly, and that’s how we got started on this piece of work.

SA: What’s the main goal of this second stage of research?

HK: With Beyond the Pioneer, we hope to start a new conversation among not just impact investors but also philanthropic foundations, aid-donor agencies, multilateral development institutions, nonprofits, governments and even companies about the challenge of scale. We all need to take a fuller, broader view of the scaling barriers faced by market-based solutions, and reassess how we can most effectively work to resolve them so that promising models can get to scale.

SA: It’s helpful, I think, to define terms. How do you actually define “scale”?

HK: It is impossible to objectively define ultimate or desired scale, except perhaps that it would meet 100 percent of the need in the world—for all practical intents and purposes, desired scale must be subjectively defined. However, in this report and the others we’ve published over the last six years, we’ve used the concept of significant scale to signify that a market-based solution is starting to benefit a large number of poor consumers or producers within a given country, and might therefore teach us something about how solutions generally scale up.

Our rule of thumb is that a solution serving poor consumers has reached significant scale if it benefits one million customers in India, or 100,000 customers in an African country, annually. This threshold applies to products for immediate consumption (e.g. safe drinking water) or involving recurring purchases (e.g. schooling), and needs to be adjusted for products that are durable (e.g. clean cookstoves) or have long-lasting benefits (e.g. cataract surgery). Meanwhile, we consider a solution engaging with poor producers to have reached significant scale if it annually benefits 30,000 producers in India, or 10,000 producers in a country in Africa.

What’s important to note here is that we are interested in the scaling of solutions and business models that work, not necessarily of individual firms, though the two do often go together, of course. This is an important point, because we believe that the growth of whole industries that are vibrant and competitive is the goal, not the creation of giant companies.

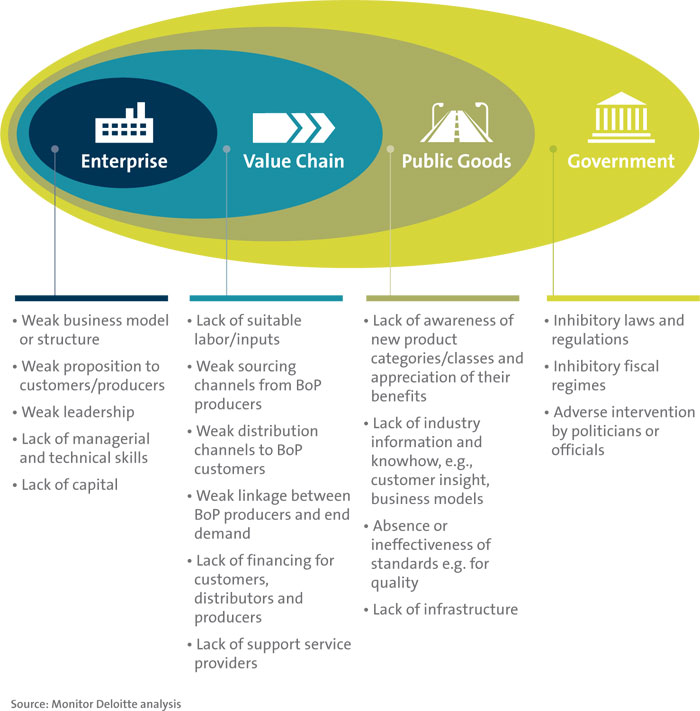

SA: You sketch out four levels of “scaling barriers,” one being inside the firm itself (such as a poor business model, weak leadership, weak value proposition, etc), but the rest being outside factors. What are those barriers?

HK: The scaling barriers start with the firm itself: it may lack money, have a weak management team, or have a flawed business model and strategy. Such problems are critical to address, and we are heartened to see that there is increasing effort being directed at these problems by investors, donors and intermediaries (such as accelerators).

But there are potentially critical barriers beyond the firm too. The first level beyond the firm is the industry value chain. Very often, firms serving the global poor find that there are important pieces of the value chain that are weak or even missing. There might not be distributors to take the firm’s products to customers who might be living in remote rural areas or in informal settlements, or lenders willing to provide financing to customers so they can buy big-ticket items such as houses or solar home systems.

There might also be barriers at the level of public goods. Consider, for example, the barriers faced by a firm trying to sell low-income customers clean cookstoves in rural India, which is technically an effective solution to the problem of indoor air pollution from cooking smoke, which kills millions every year globally. The problem is that customers don’t recognize indoor air pollution as a problem, and so don’t readily desire a solution for it. Once created, however, this awareness will benefit all the firms in the industry, hence it is a public good.

Finally, we also describe the barriers that lie at the level of what we broadly term as government, which includes laws, regulations, and taxes and subsidies, which could all potentially hinder the growth of market-based solutions. Sometimes, we find that this is because existing regulations and laws are designed in response to the needs and risks of traditional industries, and therefore inadvertently stymie the growth of innovative models.

Beyond the Pioneer provides detailed explanations of all these barriers, drawn out through in-depth case studies, and recommendations for how we can think about overcoming them.

SA: Can you provide a case in point, i.e. a company that was executing well and had investors but ran up against these barriers? (Maybe this is a failure story, or a success story in overcoming them.)

HK: A good case in point is that of M-PESA, the mobile money service provided by Vodacom Tanzania. This was a case where a large corporation was launching a service which was already being successfully operated in Kenya by its sister company Safaricom. Its initial performance was very disappointing: within 14 months of launching, M-PESA in Tanzania had just 10 percent of the number of subscribers that M-PESA in Kenya had gained after the same period. The problem was that there was really weak distribution of the service to consumers, and an industry structure that did not allow the mobile operators to fix this problem as readily as Safaricom did in Kenya. In addition, the regulator had to get up the learning curve to understand how best to regulate the growth of this new industry. The eventual success of the industry was the result of actions taken by both the firms and the industry facilitators—notably the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation and the Financial Sector Deepening Trust Tanzania—to resolve these barriers. Today, mobile money penetration of the mobile subscriber base is higher in Tanzania than it is in Kenya, and it is also more competitive and more affordable in Tanzania than in Kenya.

SA: The report is calling for an increased role by “industry facilitators” – such as foundations, aid donors, development agencies, impact investors – all of which can provide services and perhaps pressure on government barriers and/or infrastructure issues. This comes back to an ecosystem. Every market and sector is different, but how do you assess the overall role of these facilitators in terms of a BoP impact?

HK: Industry facilitation is vital because firms often cannot, and sometimes will not, address on their own the scaling barriers that they face. We analyze this in great depth in the report and also highlight it in the case studies.

The key thing to point out is that industry facilitation is a role that can be played by a variety of actors. These actors include those which you’ve mentioned: foundations, aid donors, development agencies, impact investors, industry associations, mission driven intermediaries, state agencies and parastatals, governments and even corporates. One of the main reasons why this is the case is because of the sheer variety of interventions that are often required to help scale tough barriers, going well beyond the traditional support of providing capital or capacity building. Who the best actor for the role might be depends very much on the particular barrier and the particular context in question.

Industry facilitation also tends to be an extremely local activity which requires facilitators to be on the ground, resolving barriers as they emerge. Every market, geography and sector is different and requires local knowledge and adaptation to the local context.

We realize that assessing impact of industry facilitation can be complicated. This is not only because it involves supporting an ecosystem rather than just an individual firm, but also because industry facilitation is a long term process that can take several years if not decades. It’s vital that industry facilitators plan and prepare for this length of commitment, both in terms of their overall strategy as well as in terms of how they assess results and impact.

(Above: An infographic from the Beyond the Pioneer report.)

SA: You’ve written about the report in several publications, and attended conferences and other events talking about this report. What kind of response have you received?

HK: We’re only part of the way through our dissemination campaign, but already we can tell that we’ve hit a nerve. This is clearly describing a problem that all of us have been sensing and needed some way of parsing and analyzing—as was the case when we published From Blueprint to Scale—and I’d like to think we’ve made a first step towards helping people do that. The scaling barriers framework in particular seems to have been a helpful map for people and, importantly, one that both firm-centric players (like impact investors) and systems-oriented players (like many official donor agencies and nonprofit intermediaries) can relate to. My hope is that this then helps different players see that they’re actually working on a common problem and facilitate better alignment between their efforts. Ultimately, it’s about putting these good thoughts into action, and that’s the conversation we all need to be having now.

Scott Anderson is the managing editor of the NextBillion network.

- Categories

- Education

- Tags

- infrastructure, research