In Search of the Perfect Health Care System: In India, innovators are successfully serving even the poorest communities

How can India guarantee universal access to essential health care at the community level – at costs community members and the country can afford?

It’s no surprise that the gold standard of primary care, as defined by the World Health Organization, is not being met in India. When looking at the country’s poorest states, such as Bihar, Orissa, Rajasthan and Uttar Pradesh, the health system’s performance is especially sub-par.

But there are significant lessons to be learned from private health care innovators. My colleagues and I at ACCESS Health International have been identifying health initiatives with the most relevant solutions to improve the ailing system. We hope to deduce recommendations for a better model for primary health care that works even in India’s poorest communities.

A landscape full of innovation

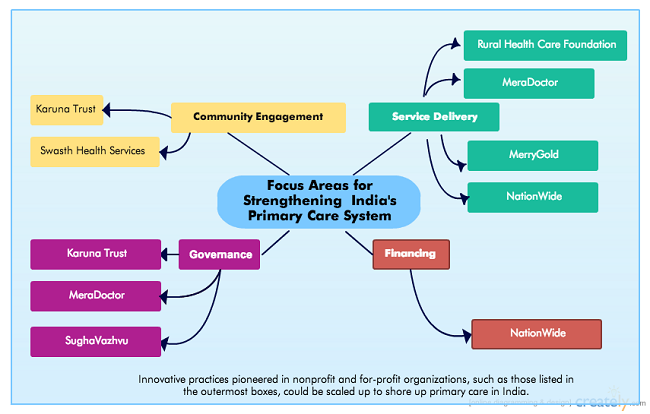

The literature tells us that the four critical pillars of a high-functioning primary care system are service delivery networks, financing, community engagement and effective governance and institutional structures. There are many holes in these pillars in the Indian scenario.

The public sector lacks infrastructure and staffing. It is overly doctor-centric even though other cadres of workers, such as auxiliary nurse midwives, could be effectively used to provide basic curative care for routine illnesses like child diarrhea and pneumonia.

Meanwhile, the private sector – representing a major part of all health provision – includes many standalone physicians and informal providers. In the absence of a strong primary health care system and effective regulation, there are many unnecessary hospitalizations and overuse of expensive, non-generic medication, leading to financial distress for many people.

Using the Center for Health Market Innovations, we identified 40 organizations innovating in primary care delivery, then narrowed our search to programs specializing in the four main pillars of the primary health system, and presented the results at a meeting in December.

In Bombay, a forum-based debate on the “ideal” model

In order to interpret our findings and gain insight, we convened academicians, program implementers and government officials in December in Mumbai at the RISE Impact Forum. The first steps to designing an ideal model, said panelists, should be maximizing the use of staff already present in the health system.

To that end, Accredited Social Health Activists (ASHAs) and Antenatal Nurse Midwives (ANMs) should be trained to assess whether cases from their communities need medical attention or could be handled by simple preventive measures. Government representatives affirmed that ANMs, ASHAs and even informal providers are invaluable players at the primary health care level. They understand that doctors are scarce and informal providers can at the least provide health education; for instance, educating women how to treat a diarrhea attack at home.

Panelists suggested several additional facets of an “ideal model”:

• Consumers have distinct and diverse values when it comes to primary care. Convenience and perceived quality are often the most important factors weighed when selecting a provider. Many prefer to interact with a known and trusted family doctor, rather than a well-known franchise brand. Rural patients may prefer to see doctors via mobile vans in their villages several times a week versus having access via telemedicine.

• To operate primary health centers, government and other financers should consider a capitation-based system with co-pay for drugs and diagnostics, which are overly costly to many consumers.

• Primary care centers may be ideally decentralized and privately run, but to avoid corruption they must be accountable to semi-governmental autonomous bodies. A model for these autonomous bodies can be found in Andhra Pradesh, where a monitoring body including doctors and biostatisticians with much autonomy governs the statewide, pro-poor health insurance program Aarogyasri.

Innovative primary care models already at work in India

To identify promising practices, ACCESS looked closely at several organizations that addressed common weaknesses in the health system and introduced a number of innovations, including Swasth India, HMRI, E-health Point, Glocal and Healthspring, plus the following organizations:

• Rural Health Care Foundation’s eight West Bengal clinics provide comprehensive care and subsidized drugs. Doctors are incentivized to practice in rural communities by being given food and lodging; many are either young or retired. The organization’s large patient volumes have enabled them to break even and even see a profit.

• SughaVazhvu is a new network of rural clinics in Tamil Nadu staffed by traditional doctors who are trained and legally permitted to give allopathic medicine. The network standardizes care with electronic medical records, strict protocols and simple diagnostic devices.

• MeraDoctor is a subscription model that targets busy urban people in the middle to upper-middle classes. Families pay a fixed fee to access unlimited tele-consultations, after which operators refer callers to physicians when necessary.

• Merrygold is a franchise network covering maternal and child health services including antenatal care, contraceptive counseling and institutional deliveries at the district, sub-district and community level. We looked especially closely at this model since they serve people in rural and urban Uttar Pradesh, a state with poor maternal and child health outcomes.

• NationWide is a chain of primary care clinics that bridges the gap between general and super specialist practitioners. They have nine clinics and 14 satellite clinics in Bangalore focusing on the upper-middle class. We’re studying the model to understand how they have built this network effect – for instance, how they are providing drugs, what protocols they use and how they retain doctors – to adapt certain practices for a BoP-focused model.

• Karuna Trust has been successful in “adopting” primary health centers in Karnataka.

Many models are breaking even in either or both the rural or urban context while delivering good quality care, and thus pose great promise to scale up high-quality, efficient care in India’s poorest communities.

Implementing the “ideal” model

Over the course of the next month, we will look even closer at these models to collect concrete evidence on how primary care can be provided in “backward” states in India. Our recommendations will be used by a donor to help implement such an “ideal” system, with technical support provided by local innovators.

What remaining questions do we have? We’d love to hear what innovators have done in other countries to design sustainable primary care models. We would welcome input from people around the world on this point.

Dr. Anuradha Katyal is a program manager at ACCESS Health International.

This article first appeared on the Center for Health Market Innovations blog.

- Categories

- Health Care