Applying ICT to Education in Africa: While Internet access expands, energy access is waning

More than 100 million school-aged children in developing countries lack access to education, and more than nine times that number of children worldwide lack access to quality education. Information, communications, and especially technology (ICT) would seem to offer feasible, less expensive, and widely applicable solutions to this complex problem.

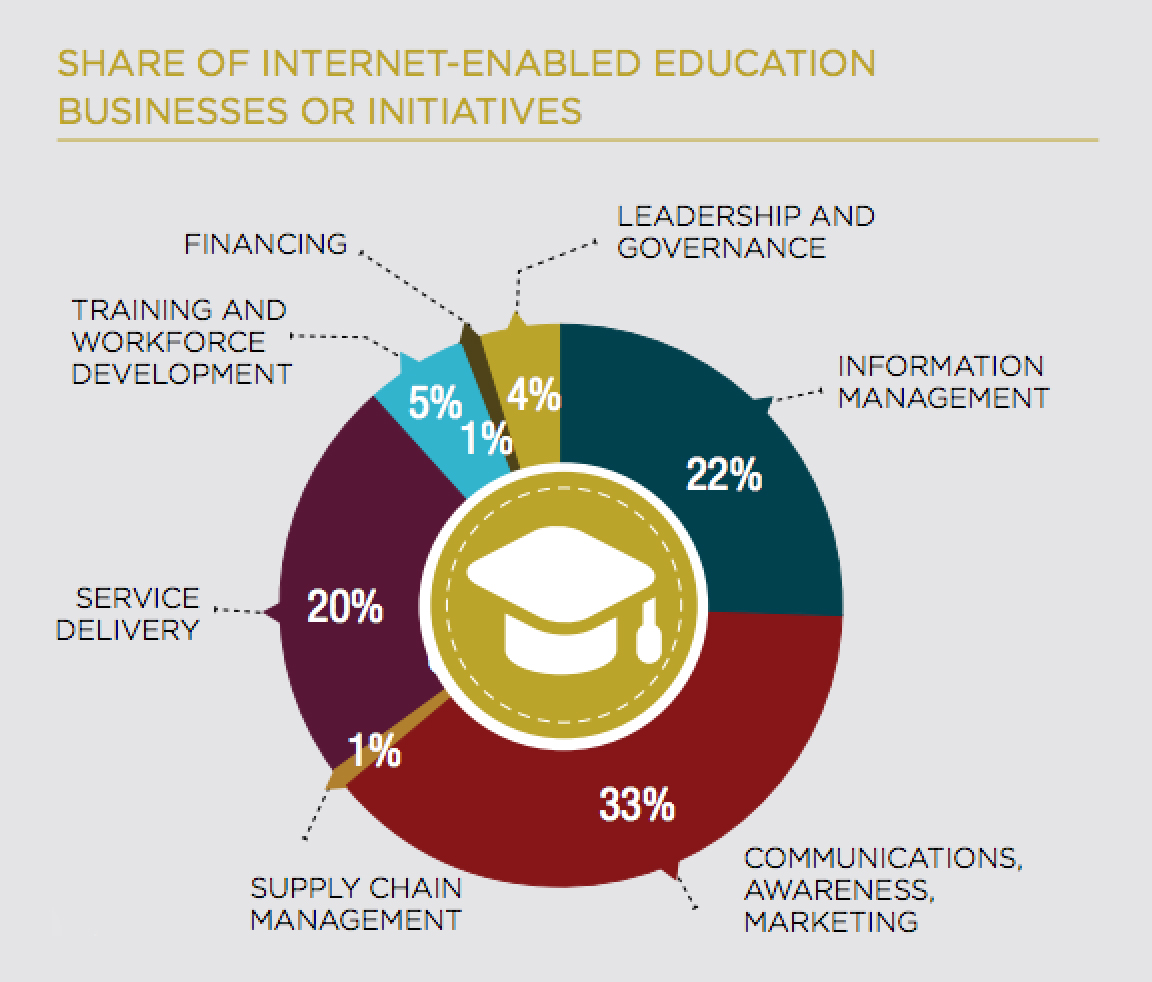

Given this potential, understanding how ICT is already being used in education is important to replicate successes. Recently, I joined a Dalberg team to produce the Impact of the Internet in Africa report, for Google. My team set out both to understand how the Internet and ICT are being used in education and to uncover ways ICTs can further improve the education sector.

The Internet’s role in storing and spreading knowledge is well known; indeed, Google itself is named after the large mathematical unit “googol” to reflect the company’s mission to organize a seemingly infinite amount of information on the web. African users agree; 60 percent of Impact of the Internet in Africa survey respondents from the education sector call the internet “essential” to their work, and nearly 80 percent believe Internet use improves access to information — in other words, their ability to acquire knowledge.

It makes sense, then, that ICT innovations are already driving increased access to education. Binu and World Reader, for example, have partnered to provide Africans with access to more 1,000 books on their smartphones. Dakar University, which has the physical capacity for just 16,000 students, now educates 75,000 students thanks to an online course partnership with African Virtual University. The Kenya National Examination Council has created online portals where students can easily register for examinations, check their results, and track their school selection process. Such online platforms have led not only to increased student convenience and lower transport costs, but also to better educational tracking.

While ICT has brought tangible positive changes in Africa, it is not always an appropriate solution for improving educational access.

(Above: An infographic from the Impact of the Internet in Africa report, conducted by Dalberg Associates, for Google. The report includes a survey of 191 education businesses or organizations across Ghana, Kenya, Nigeria and Senegal).

Africa has largely leapfrogged through several technological innovations – such as the landline phone – in the last 20 years. Typically, leapfrogging can accelerate development by skipping over a technology that may be inefficient, expensive, and environmentally unfriendly. But in the case of education technology, leapfrogging creates a few problems – at least in the short term – that mean ICTs will not necessarily improve educational access until fundamental challenges are addressed.

One such challenge is ICT literacy. Imagine a classroom of 100 young students, all with tablets tailored to their needs. Now imagine two teachers at the front of the room. Chances are, these teachers have not been properly trained to use the tablets (the ICT literacy rate is under 30 percent in rural Kenya, for example, according to an IBM Digital Villages study). How can technology help teachers’ effectiveness if they’re not trained in how to use these tools?

The rapid pace of development has also led to the spread of ICTs without the infrastructure to support widespread adoption. Many developing countries lack consistent access to energy. In 2009, almost 60 percent of Africa’s population was un-electrified, according to the International Energy Agency. Solar energy is often proposed as a solution to this challenge, but solar-powered systems have high capital costs and require technical expertise to set up. The percentage of un-electrified people on all other continents is expected to decrease in the next 20 years, but Africa is slated to see an increase in its un-electrified population — which could reach up to 700 million people.

This troubling statistic begs the question: how can ICT be an effective tool for improving education in developing African countries if access to electricity is only getting worse in these areas?

Many of the education innovations require not just electricity, but also consistent Internet connectivity and bandwidth, both of which can be hard to come by in developing countries. The Kenya Education Network (KENET), which promotes the use of ICT in education, was able to boost its effectiveness as an organization by improving its bandwidth. A grant from the government of Kenya and support from USAID and the Rockefeller Foundation helped KENET increase its bandwidth from 50 megabits per second to 2.5 gigabits per second over two years. KENET now provides cost-effective bandwidth to 114 educational institutions that reach more than 100,000 students, and 5,000 faculty and staff.

ICT can be instrumental in supporting education in developing countries, as Dalberg’s findings from the Impact of the Internet in Africa report confirmed. But an important starting point to achieve that transformation is ensuring that ICT users have access to consistent electricity and teachers with basic technological training. Given the hurdles that remain, we must view ICTs and the Internet as “tools within a holistic approach to educational transformation” – tools with potency we are already beginning to witness.

Ata Cisse is a senior consultant in Dalberg’s Dakar office and a member of the team that produced the Impact of the Internet in Africa report with support from Google.

- Categories

- Technology, Telecommunications