Learning to Love Quacks: The Untapped Potential of Informal Health Care Providers

The lack of trained medical providers has long been recognized as a global crisis. In 2006, the World Health Organization (WHO) projected a shortfall of 4.3 million doctors, nurses, midwives, and public health workers over the next two decades.

Many global health policymakers and advocates look at this dilemma, and think the answer is to train more health workers. Global coalitions, alliances, research projects, news articles, and millions of dollars in donor aid are directed to increasing the health care workforce in developing countries.

But perhaps there’s another solution.

Along with recruiting and training new health care workers, the global health community could focus on improving the vibrant and chaotic marketplace of informal providers who are already there.

An untapped resource

Informal providers—a plethora of independent and largely unregulated healthcare practitioners—are a vital source of care, making up over 50% of health workers in India and close to 96% in rural Bangladesh. Running the gamut from traditional healers and drug sellers to your run-of-the mill, roadside “quack,” these providers often lack official training and operate outside of regulatory authority.

Researchers from Bangladesh, India, and Nigeria recently gathered at the Second Global Symposium on Health Systems Research, in Beijing, to present findings about informal providers and their interactions with the broader health system.

Commissioned by the Center for Health Market Innovations (CHMI), the studies are intended to help policymakers rethink their approach to the informal health care market.

The first line of care

While they may operate outside of the formal health system, informal providers don’t hide in dark corners. According to a literature review conducted by the University of California San Francisco’s Global Health Group, informal providers are often a patient’s first point of care.

While they may operate outside of the formal health system, informal providers don’t hide in dark corners. According to a literature review conducted by the University of California San Francisco’s Global Health Group, informal providers are often a patient’s first point of care.

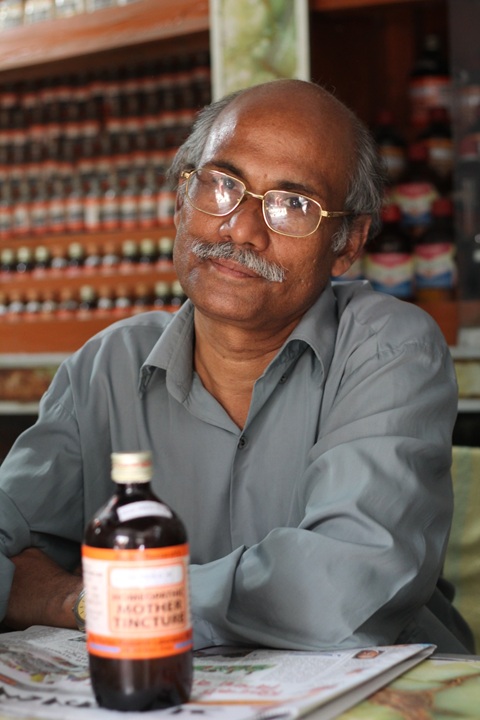

Why do patients choose them? They’re convenient, fast and affordable. In southern India, for instance, researchers found that informal providers make daily house calls on bicycles, ringing their bell much like the milk or vegetable vendors that frequent neighborhood streets. And in Dhaka, they sit at markets—like the “dentist” in the photo on the left, with rows of teeth pasted to a sign.

What’s more, their shops tend to be better-stocked with medicine than public sector providers, and less expensive than those in the formal private sector.

Researchers at the renowned Dhaka-based research institute ICDDR’B found that informal providers charge what patients can afford, and often give medicine on credit.

Trusted community members

Informal providers also have strong local roots and well-established, long-running practices. “The synergy between providers and the community they live in is very, very strong,” Nabeel Ali, the CHMI study’s lead at ICDDR’B, commented at the Beijing symposium.

Meenakshi Gautham, a researcher at the research organization Creneo and the study’s lead in India, said that more than half of the providers they surveyed were born in the same block where they practiced medicine. In Nigeria, Oladimeji Oladepo of the University of Ibadan said that the providers he surveyed for this research had practiced for an average of nine years in a community. As a result, informal providers tend to be well-respected and trusted.

Educated, trained and organized – to varying extents

Most informal “doctors” are relatively well-educated by their community’s standards, having finished secondary school or beyond.

While its duration, formality and content varies widely, most informal practitioners do have some form of health training, including commercially offered courses and public training for community health workers. In Bangladesh, for example, 91 percent of the providers studied claimed that they received some form of professional training, ranging from rural medical practitioner or medical assistant training, to family planning and pharmacist training.

Though some governments remain ambivalent or hostile to informal providers, regardless of their degree of training, others have responded by encouraging them to formalize their practices and strengthen their ties with public entities.

In Nigeria, the Private Medicine Vendor association has organized drug sellers into a strong, cohesive group with a relationship with state and federal policy makers. Their members are now trained to administer anti-malarial drugs and sell insecticide-treated nets.

Similarly, medical providers operating in rural Andhra Pradesh have created a self-registration system, and regularly lobby government through 11 professional organizations, some that have been operating since the 1960s.

However, in Bangladesh, our study showed that “quacks” don’t have much of a voice with government. Though the study focused only on three countries, this situation is likely common in many other countries as well.

Organizing the chaos to improve care for all

Like many in the formal health sector, informal providers lean heavily on prescribing and selling drugs—for example, giving steroid injections for a headache, as this analysis of informal health markets explains. They also tend to administer other harmful, unnecessary and wasteful services. (Unfortunately, the formal sector often shares many of these flaws. In India, for instance, both public and private providers are unlikely to follow appropriate treatment protocols.)

Like many in the formal health sector, informal providers lean heavily on prescribing and selling drugs—for example, giving steroid injections for a headache, as this analysis of informal health markets explains. They also tend to administer other harmful, unnecessary and wasteful services. (Unfortunately, the formal sector often shares many of these flaws. In India, for instance, both public and private providers are unlikely to follow appropriate treatment protocols.)

So what’s the best way to improve informal providers’ services?

At the Beijing symposium, moderator David Peters from the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health suggested that more long-term studies could provide a basis for effective policies, which could be implemented and tweaked to respond to the dynamic forces of informal markets.

For instance, if studies show that providers lack resources to purchase laboratory equipment, and thus diagnose by sight, financers (governments, donors or investors) could supply portable, inexpensive diagnostic tools.

But the key to improving informal providers’ services may be to influence their practice through their trusted sources of information. Studies like those discussed in Beijing, along with other related studies, can be useful in identifying these sources.

For example, if we knew that informal providers occasionally sought advice from formal providers, hotlines—like one that has been deployed in Bangladesh—could connect them with sources of appropriate medical information. Many initiatives are now providing technology tools, like D-tree and CommCare, to community health workers employed by the government. These tools could also be useful in the hands of informal providers, if they had the right training and incentives.

Informal providers aren’t going away – and in many communities, they’re the most attractive (or only) option for health care. Perhaps by harnessing these accessible, affordable and trusted providers, policy makers could expand quality care to their citizens and move one step closer to universal health coverage.

Can informal providers help attain universal health coverage?

Researchers from India, Nigeria and the United States respond in these videos.

- Categories

- Education, Health Care

- Tags

- research