Sisi ni Amani: An Experiment in Marketing Peace

At the BoP, we use marketing for lots of things. We market products like shampoo sachets and fertilizers; we market services like pay-per-use toilets and private ambulances; and we even market behaviors like ’send your child to school’ and ’don’t have unprotected sex.’ We rely quite a bit on the power of marketing. But just how far could we take it?

Could we market, say, peace?

On Aug. 13, an NGO called Sisi ni Amani – Kenya (’We are Peace’ in Swahili) sent an SMS message to its 10,000 subscribers across Kenya: “A good leader initiates and encourages peace and development among all people and is not tribal.” In a nation divided along ethnic lines, where a winner-takes-all mindset fuels rampant corruption and political violence, changing perceptions of good leadership is a daunting endeavor.

And yet, according to post-campaign data, 90 percent of respondents said they changed their understanding of ’what makes a good leader’ in response to the organization’s messaging. As one respondent commented, “I used to think a good leader is one who has the most votes, but now I know a good leader is one who thinks of the people who voted for him, not himself.”

Rachel Brown founded Sisi ni Amani – Kenya (SNA-K) after the post-election violence that rocked Kenya in 2007-8, killing 1,200 and displacing more than 300,000. During the unrest, violent actors used mobile technology to spread hate speech and organize attacks. Marketing aims to shape mindsets and influence behavior through mediums of communication (like cell phones), which is exactly what the perpetrators of violence had mastered. So why, Brown asked, couldn’t we use that same approach to market peace? According to Brown, “there is a need to tap into these same communication channels, particularly mobile phones, to prevent and de-escalate tensions and violence.”

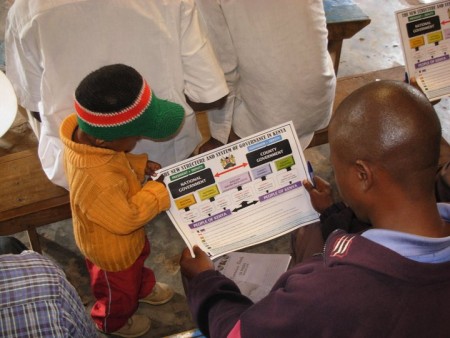

Today, SNA-K uses the communications power of SMS to market peace and, more tangibly, to bring Kenya’s marginalized civilians into the political fold. For example, months before an election starts, SNA-K local chapters organize workshops with community leaders to craft SMS messages on voter education. Leading up to election day, the messages are broadcast to mobilize voter turnout and remind subscribers of voting details, turning disenfranchised citizens into active, educated and peaceful voters.

The organization makes a compelling case for SMS as a marketing medium at the BoP. Marketers are constantly on the hunt for breadth and depth, reaching mass audiences in the most personal ways possible. As Brown reflected in a recent interview, “not only do texts come directly to you, but it’s common practice among Kenyans to share them with friends and family. It allows us to reach lots of people in a very personal way.”

Not only is it personal and far-reaching, but it’s also cost-effective and authoritative. As Brown noted, whereas aid agencies often pay for a billboard advertisement, SNA-K can reach tenfold the people and generate far more buzz for a fraction of the cost with SMS. It’s also authoritative: in Kenya, Brown explained, information through SMS is viewed as trustworthy – especially when it comes from a respected brand like Sisi ni Amani.

Of course, these reflections on SMS aren’t alien to the BoP community (this publication in particular has exhaustively covered the innovative uses of mobile technology, from mobile money to e-health). But in a context where entrenched corruption and hovering violence battle against development, empowering the poor as peaceful political participants through mobile marketing is a radical and welcomed innovation.

Please like NextBillion on Facebook, follow us on Twitter and/or join our LinkedIn group.

- Categories

- Uncategorized