The (BoP) Project: Finding Sustainable Water Solutions

Editor’s note: Jonathan Kalan, photojournalist and writer continues his efforts to chronicle innovative social enterprises in East Africa with The (BoP) Project: Photojournalism at the Base of the Economic Pyramid. The series was first introduced on NextBillion here.

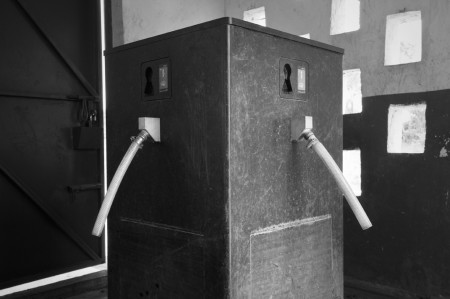

(Above: Grundfos LIFELINK, the first solely BoP-targeted subsidiary business from pump manufacturer Grundfos. All images by Jonathan Kalan).

Over one billion people in the world have no access to clean water, or must travel several kilometers each day to fetch it, only to carry heavy buckets and jerrycans full, back the same distance. This job, almost always, is done by women.

Water is not just needed for drinking. It’s needed to cultivate and nourish crops, raise livestock, and run small businesses from tea stands to clothes washing. For those at the BoP, water is truly a means of livelihood, and the overall economic loss due to lack of access to safe water and basic sanitation in Africa alone is estimated at $28.4 billion a year, or close to 5% of Africa’s GDP.

In many areas, there is but one solution: build a well. Depending on the size and power (manual or electric) of the well, an organization or community can drill a borehole and install a pump system for a $5,000 – $20,000 USD initial investment. But once a community has a well, many questions remain. Who will maintain it? Who will pay for repairs? Who will monitor the health and water table of the well? Sometimes, the answers are not always clear, and wells far too often go dry or remain broken.

Now, picture a world in which clean, safe, and affordable water is available to everyone- especially those at the Base of the Economic Pyramid who are living in dry, semi-arid regions on less than $2 USD a day.

As our car bounced up the road (“road” being a very generous term here…) to the small village of Wendano, Kenya, I no longer had to picture a solution. As we approached an empty patch of land, out of the corner of my eye I spotted a giant water tower stretching up towards the sky, topped off with a clean-looking solar panel. At the base, stood a small concrete structure; centered inside was a four-foot high black box with 4 hoses sticking out. From afar, I thought I was looking at some sort of strange robot.

The Grundfos LIFELINK system is certainly no robot, but it is about as high-tech as rural water solutions can get. The LIFELINK System is a single-point water supply system with a submersible pump that is powered entirely by solar panels; the water is pumped to an elevated storage tank, then led by gravity to a tap unit in a small, secure concrete housing structure. The tap unit (the big black box) also serves as an automatic payment facility, utilizing a unique mobile payment system (M-PESA) and a pre-paid FOB key (with Radio Frequency Identification Technology), which can be re-loaded and paid by customers through a simple text message. The whole system contains a computer-based communication and surveillance module, relaying real-time usage, water table health and operational information. Check out one of the systems I visited HERE.

(Above: Redemta Ndanu (above), of Wendano, Yatta District, Kenya, checks the balance of her prepaid key fob after filling up. Her husband works in the city, and transfers money to her via M-PESA, a mobile payment system. She then transfers the money via text message to Grundfos LIFELINK, topping up her prepaid balance).

Grundfos is responsible for providing maintenance, repairs, and replacements. In its contract with the community, the consumers agree to pay a 2 or 3 KSHs/filling fee (depending on the location) and Grundfos guarantees they will fix or replace any parts of the system that may breakdown. (Hence the need for all the monitoring).

(Above: Jacinda Mortinda Paul, owner of the “Hot Hoteli”, a one room shop that serves hot tea, cooked food, and small snacks, uses 7 jerrycans of water each day to run her business. Previously, she walked 4-5km to the river to get water or paid someone 10 KSH/jug to bring water. Now she only pays 3 KSH, and walks just 1/2 a kilometer).

Grundfos LIFELINK is a business, not a charity, as the promotional materials quickly point out. It is the first solely BoP-focused subsidiary business from the world leading pump manufacturer Grundfos, which has spent two years piloting the LIFELINK system, a market-based approach to solving the issues of water poverty. According to their mission, they are “committed to improving the living conditions for the disadvantaged people in the BoP market by providing them with access to safe drinking water and other infrastructural platforms.”

At only 2-3 Kenyan Shillings (around $.04 USD) per jerrycan, the price recommended by the Kenyan Government, the LIFELINK system is both affordable and accessible to those at the BoP. Yet with an initial price tag of close to $35,000 per system, the LIFELINK solution is certainly not a cheap investment. But, in the end, the incredible sustainability of this system may more than make up for the price. As long as the sun keeps shining, consumers to continue to pay, and Grundfos continues its close monitoring, maintenance, and service of the equipment through the funds generated, these systems can last upwards of 20 years.

(Above: Jacinda Mortinda Paul, owner of the “Hot Hoteli”, a one room shop that serves hot tea, cooked food, and small snacks, uses 7 jerrycans of water each day to run her business. Previously, she walked 4-5km to the river to get water or paid someone 10 KSH/jug to bring water. Now she only pays 3 KSH, and walks just 1/2 a kilometer).

In theory, at the cost of $35,000 a system, a village of 2,000 people would only need to pay $17.50/person up-front for the system, or less than $1 per person per year for 20 years, in addition to the service fee. While currently aid agencies, NGOs and governments are purchasing or investing in these systems, not the communities themselves, it seems like if managed properly, the communities could possibly bear the costs. Grundfos LIFELINK said that working with microfinance institutions to do just that was part of the initial model, but their current approach made more sense for piloting the system.

While the 9 systems currently operating around Kenya certainly won’t be able to sustain Grundfos LIFELINK’s operating costs, at scale- great scale-Grundfos feels it may just have discovered a financially viable solution to providing clean water to the BoP.

With a market of over 1.1 billion people waiting for a solution, I hope they have found it as well.

(Above: The LIFELINK System in KMC, a dry and dusty town on the outskirts of Nairobi, serves over 3,000 community members. Here, a steady demand of jerrycans is waiting to be filled).

- Categories

- Agriculture, Environment