Taking Stock of India’s Fintech Landscape: A Venture Capital Firm Shares Six Insights from One of the World’s Most Vibrant Investment Markets

Quona’s global team recently embarked on an inspiring visit to India, bringing together colleagues from the U.S., Brazil, Mexico, Singapore, South Africa, Kenya and the UAE. A venture capital investor focused on inclusive fintech, we are firm believers in the value of global perspectives, so we immersed ourselves in the Indian fintech ecosystem with the guidance of our local Bengaluru-based team.

Over two weeks together in India, we engaged with numerous founders of our portfolio companies, heard impactful stories from their customers and exchanged insights with fintech thought leaders. Reflecting on our experiences in various local markets around the country, we emerged from this expedition more energized than ever in our mission to collaborate with exceptional founders utilizing groundbreaking business models to drive financial inclusion across the globe.

Here are some of our team’s key takeaways about current trends, challenges and opportunities in India’s financial services market.

1. India represents a long-term growth opportunity like no other

A unique combination of factors positions India as one of the most attractive opportunities in the current global investment landscape. With over 1.4 billion people, predominantly young and internet-savvy, and a GDP of US $3.4 trillion, India has the largest population in the world (having recently surpassed China) and represents the world’s fifth-largest economy. Over the past two decades, the country’s income per capita has grown by a factor of 3.7 (purchasing power parity adjusted), raising millions of people out of poverty.

But in spite of this growth — and the success of government programs in boosting access to basic banking services — structural problems abound, and access to quality financial services remains a privilege of the few. To put it into perspective, credit penetration is only 50% of GDP (compared to the global average of almost 144%), whereas 6% of Indians have access to private health insurance and less than 9% to a brokerage account, according to our analysis. Nevertheless, India’s high-energy and ambitious entrepreneurial ecosystem, driven by a world-class talent pool, provides the country with the innovation it needs to tackle persistent challenges and create unprecedented value for fintech investors, consumers and companies.

2. Rural vs. urban dynamics have created contrasting realities

As much as 64% of India’s population lives in rural communities, a staggering contrast to other developing economies like Brazil (12%) and Mexico (19%). And unfortunately, educational, employment and entrepreneurship opportunities in rural communities are nowhere close to those found in cities.

One issue long faced by India’s rural farmers has been the unpredictability of pricing and storage for their goods; historically farmers have only been able to sell their goods in markets close to their locations, which means they have access to less competitive prices.

One company that aims to address this problem is Arya, which provides an end-to-end integrated solution for small and medium-sized farms. Arya’s solution enables farmers across India — whether they’re rural or closer to cities — to safely warehouse their goods, secure financing, and make their produce available to larger buyers around the country via a digital marketplace. By allowing farmers to avoid selling when prices are low right after the peak in supply that follows a crop, Arya has helped more than 650,000 farmers to increase their earnings by 15-40%.

Nearly 10 million Indians migrate to urban centers in pursuit of better opportunities each year, with megalopolis such as Delhi approaching 34 million inhabitants. But the infrastructure in these cities hasn’t kept up with increased urban density, which has led to immense challenges: Air pollution is at the top of the list, with India being home to the four most polluted cities in the world. Unfortunately, this problem is worsening — and urban populations are urging improvements.

We believe that the combination of climate technology and financial services can play a pivotal role in advancing solutions that can improve the quality of life for those who reside in urban areas. One example is the Quona-backed enterprise Turno, which offers ownership solutions for electric commercial vehicles, encompassing commerce, financing and after-sales management. With a focus on the three-wheelers (“tuk-tuks”) that are ubiquitous in India, Turno helps customers to convert to electric alternatives by alleviating upfront costs through financing, enabling a shift away from combustion engines that can reduce the operating expenses of running their vehicles by as much as 50%.

3. Micro and small shops remain the heart of India’s economy

Micro and small retailers are the backbone of India’s economy, to an even greater extent than they are in other emerging markets where Quona invests. While much of their economic contributions remain informal, they are estimated to represent approximately 33% of GDP and 40% of the workforce. Entering into a typical Indian shop is a bit of a paradoxical experience: With multiple QR Codes on the counter enabling customers to seamlessly pay with India’s pioneering real-time payments system (known as Unified Payments Interface or UPI), one can easily overlook the level of informality and lack of access to quality services faced by merchants. Despite the availability of these tech-driven systems, most businesses still run their operations on pen and paper, and struggle to access extended payment terms to purchase inventory.

We are excited about the founders who are building innovative solutions to address these needs, such as Rupifi. With a business-to-business (B2B) payments network that leverages UPI’s rails to serve B2B distributors that range from large e-commerce platforms to offline small and medium enterprises, the company has enabled more than 100,000 merchants to frictionlessly access extended payment terms for much-needed inventory purchases.

4. Regulation represents challenges and opportunities

India’s government has been rightly praised for spearheading ambitious projects that succeeded in pulling hundreds of millions of Indians into the digital economy. Aadhaar, India’s universal identity system, was launched in 2010, and now covers around 95% of the population: It has played a crucial role in enabling the digital authentication and onboarding of internet users. Meanwhile, UPI, introduced in 2016, has significantly transformed the landscape of payments, offering instant, 24/7, cost-effective and seamless digital transactions. This digital public infrastructure has reduced transaction costs and enabled numerous business models to emerge, from e-commerce to payment-led super apps.

India’s regulators have thoughtfully promoted an agenda that carefully aims to balance innovation with consumer protection. For instance, the country has followed a similar approach to Brazil (another of Quona’s core markets), which has innovated by allowing companies to apply for tiered licenses for specific financial services, which are quicker and less costly to obtain than a full banking license. These initiatives have been key to propelling financial inclusion forward, with an unprecedented 96% of Brazil’s adult population having access to digital banking services in 2021, up from 55% in 2010. (A more in-depth discussion on this topic can be found in this piece, published last year).

Similarly, in India, while there are only 46 banks with a full broad-based commercial license, there are more than 100 banking institutions when including the Small Finance Banks, Payment Banks and Regional Rural Banks that operate with lower-tier licenses. India also has nearly 9,400 non-banking financial companies (NBFCs), which have become instrumental in the country’s credit ecosystem. As a result, India’s fintechs have learned how to partner and work closely with its banks and NBFCs. Some of Quona’s recent investments capitalize on this trend. Shivalik Bank, for instance, is a fully licensed bank powering digital platforms in a variety of sectors through its banking-as-a-service (BaaS) offering. Upswing, on the other hand, is a horizontal BaaS connector, partnering with financial service providers (such as Shivalik) to embed these providers’ products into digital platforms run by other companies, thereby enabling these companies to offer their customers solutions ranging from fixed deposits to credit cards and personal loans.

Given the Quona team’s global remit, we often approach market-specific financial solutions with a desire to compare and contrast them. Applying that lens to Brazil and India, while Brazil’s analogue real-time payment system, PIX, allows payment service providers to charge for a variety of transactions (i.e., consumer-to-business and B2B), the UPI system has opted to remain completely free: So if a payment transaction is conducted via UPI’s rails, the service provider cannot charge for it. In spite of this potential headwind, Indian entrepreneurs have found ways to incorporate this infrastructure into their businesses. While directly monetizing UPI is not a possibility, many startups have built successful models around it. Leveraging UPI as a “hook” to drive user acquisition and engagement, decacorns such as PhonePe and Paytm have succeeded in monetizing users by cross-selling them adjacent services, such as credit, e-commerce and insurance.

5. Business models in India are very different from elsewhere

India is a game of scale. With a GDP per capita that’s a fraction of that of more developed economies — and even of other developing nations — it requires lots of users to build commensurate revenues. In addition, operating at a national level is no easy task, particularly considering India’s sheer diversity of cultures, languages and customer preferences.

Moreover, the country’s monetization and profit pools can differ significantly relative to other economies, as discussed above. For example, scan through a financial statement of any credit company in India and you will find stark differences from a comparable company in Latin America: While interest rates and net interest margins are significantly lower in India, so are credit losses. In our view, amongst other factors, lower credit defaults are reflective of India’s more risk-averse, savings-oriented culture — signs we also see in segments such as wealth management and insurance.

As a result, to succeed in India — either as an entrepreneur or as an investor — a deep understanding of its complex, unique and multifaceted nuances is required.

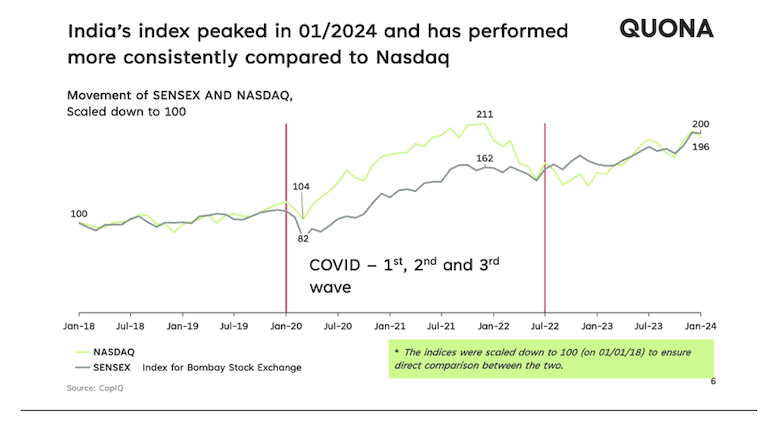

6. Equity capital markets in India have substantial depth, but there’s an opportunity on the debt side

With a combined market capitalization exceeding US $4 trillion, India’s stock market has substantial depth. Indian equities have performed strongly, up nearly 90% in the past five years, with a price to earnings ratio of 22.4x: This ratio (which goes up along with the cost of a stock) is greater than the average among emerging markets equities (11.8x) and even greater than the ratio among U.S. equities (20.4x as of February 2024). In the past years, large tech unicorns have debuted in the public markets, including Paytm, Zomato and Policybazaar. Although post-IPO stock performance has been mixed, this is a reality shared by markets across the globe, especially evident in listings during the bull run from 2020 to 2022. As investor interest in IPO markets grows, we expect local and foreign listings to become an increasingly attractive source of liquidity for the local startup scene in India.

On the debt side, however, we believe that there’s an opportunity to draw inspiration from precedents set by other markets. In Brazil, for example, securitizations and other flexible financial instruments backed by pools of different types of receivables (such as invoices, real estate or agriculture) have become popular fixed-income investment alternatives among lenders and investors. This has allowed emerging companies to tap into attractive off-balance sheet financing at large scale — and has arguably been a core reason for the country’s ascendant credit availability. While such structures aren’t as common in India today, there’s an opportunity for regulators, lenders, investors and platforms — from wealth management companies to capital markets infrastructure providers — to build a flourishing debt capital markets ecosystem, as has already occurred on the equity side.

Looking forward

Inspired by its beautiful landscapes, diverse culture and amazingly welcoming people, we concluded our expedition to India absolutely energized to continue to support the new generation of founders who are building the future of this incredible country. Whether it involves opportunities to build more BaaS solutions, create embedded finance tools to bring more of the country’s population into environmentally sustainable practices, or develop solutions that can help rural communities thrive, we are excited to see — and invest in — what’s next for India.

Michel Zaidler is a venture capital and growth equity investor at Quona Capital.

Photo courtesy of CCAFS/2014/Prashanth Vishwanathan.

- Categories

- Agriculture, Finance, Investing, Technology